In an attempt to reach beyond the traditionally high-class art audience and into the public sphere, the Dadaists worked across many new and experimental media. In addition to the many famous photomontages for which the movement is best known, Dada works also include performances, lectures, magazines, journals, caricatures, posters, assemblages, confrontational poetry, noise concerts, leaflets, and many traditional art forms1. Language plays a crucial role in many of these mediums; and while usually discussed less than the aesthetic components2, it is extremely important to the movement as a whole. The Dadaists attempted to completely revolutionize language through a radical manipulation of language itself, the presentation of language through typography and layout, and the distribution of language through various publications. This manipulation of language allowed the Dadaists to create a provocative disorder in mass media that attempted to breakdown the static bourgeois political and cultural state of the Weimar Republic.

Although it is generally remembered for its radical politics, the Dada movement initially began in 1916 in Zurich without any specific political agenda as more of an intellectually based moral protest3. The Dadaists were appalled by the fact that the current values and traditions of society had not only allowed for the inhumanity of World War I to occur, but had actually caused citizens to clamor with excitement at the very idea of fighting for their country4. This deep seeded “creative doubt” created within the Dada artists an overwhelming desire to rip apart the current atrociously bourgeois culture to a point where it could then be completely rebuilt. In order to effectively breakdown culture they had to produce an anti-culture. And thus Dada, the anti-art was created5.

The unraveling began as the Dadaists started to question the basic fundamental building blocks of culture - language. “Doubting the validity of language and all established grammar6” brought Huelsenbeck and Ball, two of the founders of Zurich Dada, to the creation of sound poetry (Cat. 30). The sound poems consisted of different combinations of letters that would then be performed for an audience7. By stripping language down to only the most basic components, the artists hoped to demonstrate to the audience how words themselves were being used as tools for upholding the ruling value systems and power structures8. Hugo Ball believed that the word had been turned into a base commodity by religion, art, western culture, and that true change would require a reversal of this commodification process. These poems reduced the word to nothing, which Tristan Tzara claimed to be the true subject of Dada - nothing9. These linguistic experiments became a complete absence of culture, forcing the current culture into perspective.

The found word poems were another influential linguistic component in the Dada movement (Cat. 31). These poems adapt the language of advertising using sentences, phrases or words found from various magazines, posters, newspapers and other modes of mass communication. Every line is typographically diverse which allows the viewer to understand that the elements of the poem are collaged together. By using only found material, he is resisting the logic of “the rules of linguistic or poetic order10. In this way, these literary collages act similarly to the sound poems in that they are a rejection of cultural order and status quo. These works communicate to the viewer in the familiar language of commerce and commodity. Through this radical use of typography, Tzara demonstrates the commodification of language in everyday life and its use as a tool in capitalist structure.

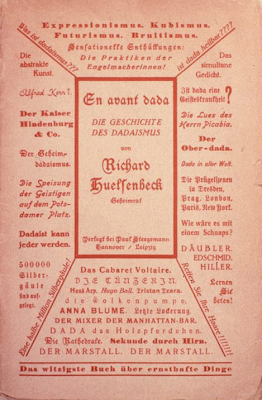

After experimenting with these different aspects of language, the Berlin Dadaists then implemented these techniques in several Dada Publications (Cat. 32, Cat. 4), which were used to distribute their anti-war and anti-nationalist political ideologies11. In contrast with Zurich Dada, Berlin Dada was formed in 1918 right at the end of World War I12. The social, political, and economic state of post-war Germany was an everyday reality for the artists living in Berlin. And although the German monarchy had been overthrown and a socially democratic government had been established, the political beliefs that supported the war continued to rule the state. The Berlin Dadaists hoped to refuel the revolution and began to create propaganda (Cat. 35). The political activism can be seen in the violent proposals of Tzara’s Manifesto dada 1918, which calls for a complete abolition of logic13. The radical language of these publications becomes even more startling and eye catching as they use layout and format to really grab and hold onto the viewer. Through variations of font, directionality, color, size, varied weight, and generally unconventional layouts of these publications, they infiltrate the everyday German life. These magazines act as newspapers, allowing the Dadaists to easily disseminate their political programs. Here they leave the art world, crossing almost completely into the public sphere with the goal of total transformation (Cat. 33, Cat. 34)14.

Not only did Dada directly influence the everyday life and culture of the Weimar Republic, but also many Dada artistic principles or devices affect almost all contemporary art, music, and literature in some way or another15. They are responsible for breaking down the boundaries between high-art and everyday life. Their experiments with typography and collage have permanently altered advertising and propaganda. Their anti-bourgeois revolutionary spirit lives on in every purely conceptual artwork or happening that rejects the value of the art object as commodity16. The Dada movement has ended, but the protest continues.

1 Mathew Biro. The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin. (Minneapolis, MN, 2009), 26 .

2 Mathew Biro. The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin, 27.

3 Richard Huelsenbeck. Memoirs of a Dada Drummer, Edit. Hans J. Kleinschmidt (1969), 137.

4 Richard Huelsenbeck. Memoirs of a Dada Drummer, xxiii.

5 Richard Huelsenbeck. Memoirs of a Dada Drummer, xviii.

6 Richard Huelsenbeck. Memoirs of a Dada Drummer, xxiv.

7 Richard Huelsenbeck, Dada Almanach, v.

8 Richard Huelsenbeck, Dada Almanach, vi.

9 O. B. Hardison Jr. Dada, the Poetry of Nothing, and the Modern World (1984), 387.

10 Johanna Drucker. The Visible Word: Experimental Typography and Modern Art, 1909-1923. (London, 1994), 194.

11 Richard Huelsenbeck. Memoirs of a Dada Drummer, 137.

12 Mathew Biro. The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin, 28.

13 Richard Huelsenbeck, Dada Almanach, v.

14 Mathew Biro. The Dada Cyborg: Visions of the New Human in Weimar Berlin, 27.

15 Richard Huelsenbeck. Memoirs of a Dada Drummer, li.

16 Timothy Shipe. "The Dada Archive" in Books at Iowa, no. 39. (November 1983).